DownUnderCTF: zeus

Room recap:

Zeus was a room packed with new and challenging concepts for me. To retrieve the flag, I had to reverse an XOR encryption algorithm embedded in the program’s binary. The main tool that helped me accomplish this was Radare2 (R2), which disassembled the binary into readable assembly code.

I also experimented with tools like GDB, Binwalk, and Objdump, but none of them yielded results as effectively as R2 did in this case.

Room link:

Key Takeaways

🧠 Learned how to convert binary to hexadecimal.

💫 Gained experience in analyzing binary files using tools like Radare2, Objdump, and others.

💫 Gained a deeper understanding of the XOR process and how a hexadecimal value is represented in binary.

💻 Used Radare2 to extract and interpret assembly code from compiled binaries.

💻 Used tools like Strings to locate printable text strings embedded within the file.

Ight. Let’s do this!

Since this is a reverse engineering room, there’s no website to interact with.

Just a single downloadable file named zeus.

After downloading the file, I ran a command to inspect its details:

1

file zeus

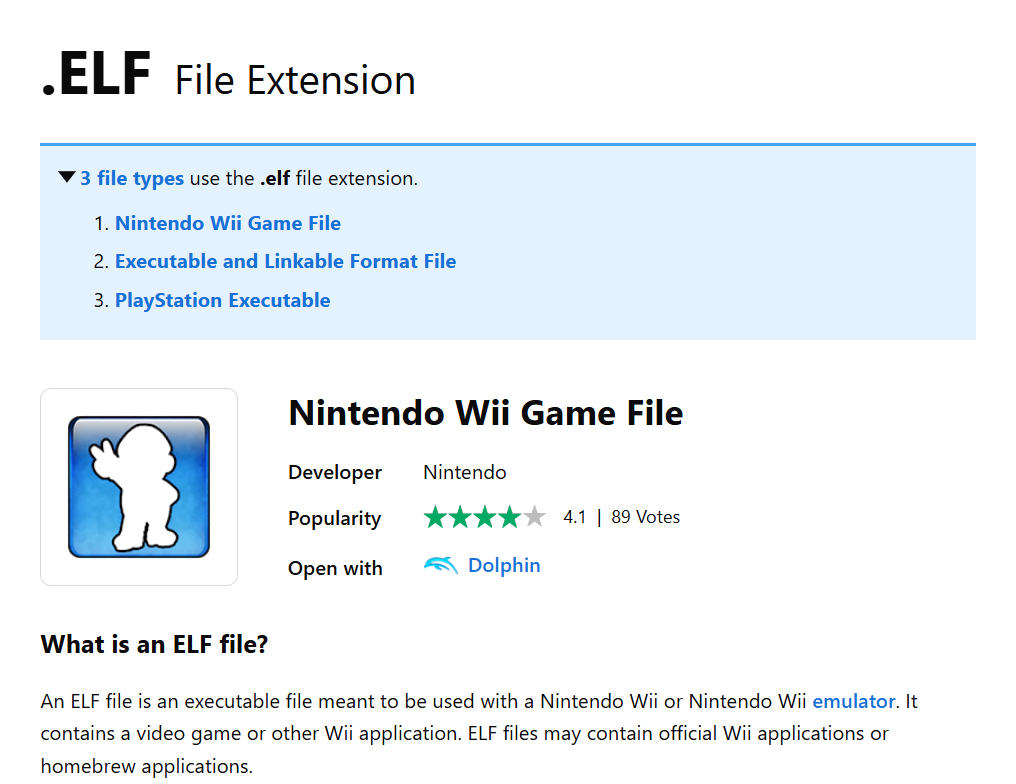

The output showed a file type that I wasn’t very familiar with in the context of CTFs.

1

zeus: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=95542c1d888f30465172c1c77dd1eef1109b4c29, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

So, I visited fileinfo to dig deeper and found the following information:

From the site’s description, I assumed that this file behaves similarly to a .exe, so I went ahead and tried to execute it:

1

2

./zeus

The northern winds are silent...

The result? Just a single line: “The northern winds are silent…“ Uhhh, yeah…not really helpful is it 😔.

Curious, I was going to “cat” the file, fully expecting it to spew out a bunch of unreadable characters (it’s a binary after all). So instead, I opted to use the “Strings” command to extract all human-readable text embedded inside the binary.

While skimming through the output, one block of text caught my attention:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<SNIP>

To Zeus Maimaktes, Zeus who comes when the north wind blows, we offer our praise, we make you welcome!

Maimaktes1337

-invocation

Zeus responds to your invocation!

His reply: %s

The northern winds are silent...

<SNIP>

This snippet felt like a clue. The line “Zeus who comes when the north wind blows” directly contrasts with “The northern winds are silent…”—which was the exact message we saw earlier when executing the file.

It made me think: maybe we haven’t triggered the correct condition yet.

There were two other notable things in the strings dump:

- A command-line-like argument: -invocation

- A potential password or passphrase: Maimaktes1337

From here, my theory was: If we pass the correct argument (like -invocation) along with the keyword Maimaktes1337, Zeus might actually reply—with the flag.

Putting it all together.

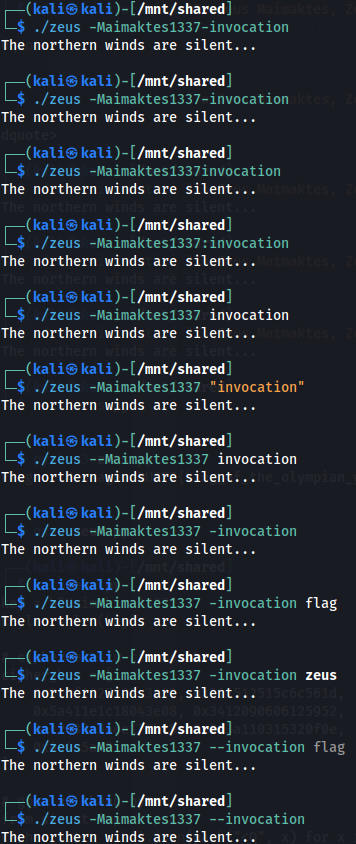

Time for action. I tried running:

1

2

./zeus -invocation Maimaktes1337

The northern winds are silent...

…and nothing.

What followed was a solid 30 minutes of me swapping the order of -invocation and Maimaktes1337, trying every possible combo like i was paid to do it 😭🙏. (the image below was a SNIP of the process)

Still nothing.

At that point, I figured brute experimentation wasn’t going to cut it. So I decided to reverse the binary and dive deeper into its internals—maybe I’d uncover what exactly triggers the flag.

The hidden X*R

After analyzing the binary’s logic with the help of AI and tools like objdump and radare2, I came to a few key realizations.

To retrieve the flag as intended in this challenge, the binary expects exactly three arguments, including ./zeus. This means two additional parameters are required, like so:

1

./zeus <arg1> <arg2>

However, as you saw from my earlier brute-force attempts…that path leads nowhere fast. Trial and error isn’t our friend here. 😅

Digging deeper into the assembly code, I found both the main function and a separate XOR function. Here’s the breakdown:

the XOR function

The XOR function implements a repeating-key XOR: it takes a 51-byte ciphertext and XORs it byte-by-byte with a 13-byte key, repeating the key as needed.

And here comes the twist: the string “Maimaktes1337” is exactly 13 bytes long. Jackpot. That’s the hardcoded key, and clearly it’s meant to be used for decryption—likely of the flag.

the MAIN function

In the main function, I noticed some hardcoded ciphertext arrays. These get passed to the XOR function—but only if the input arguments meet specific criteria. If they do, the decrypted result (presumably the flag) gets printed.

How it’s done!

So now we have a clear strategy. Instead of playing guessing games with inputs, we can:

- Extract the ciphertext directly from the binary,

- Use “Maimaktes1337” as the key,

- XOR-decrypt it to recover the plaintext flag.

To automate this, I whipped up a simple Python script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

# zeus_solve.py

def xor_decrypt(data, key):

keylen = len(key)

return bytes([b ^ key[i % keylen] for i, b in enumerate(data)])

def main():

encrypted = [

0x09, 0x34, 0x2a, 0x39, 0x27, 0x10, 0x1f, 0x0c, 0x1d, 0x56, 0x6c, 0x5c, 0x51,

0x12, 0x15, 0x01, 0x08, 0x3e, 0x04, 0x18, 0x1c, 0x1e, 0x41, 0x5a, 0x52, 0x59,

0x12, 0x06, 0x06, 0x09, 0x12, 0x34, 0x15, 0x0b, 0x17, 0x6e, 0x54, 0x5c, 0x53,

0x12, 0x0e, 0x0f, 0x32, 0x15, 0x03, 0x11, 0x3a, 0x00, 0x5a, 0x4a, 0x4e

]

# the key that was hardcoded in the original code

key = b"Maimaktes1337"

decrypted = xor_decrypt(encrypted, key)

print("Flag:", decrypted.decode())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

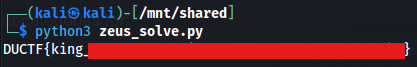

And tadaaa! Running the script gives us the flag instantly:

Anddd that’s a wrap on this room!! 🗣️😁

Optional read…

Explain on how i got the “encrypted” array full of hex bytes.

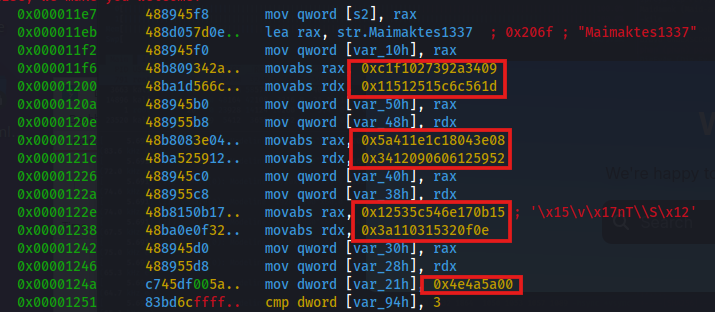

As i said before while using tools like Radare2 and Objdump, I noticed several large 64-bit hexadecimal integers (that MIGHT be the ciphertext that the XOR function used) embedded directly in the “zeus” file like this:

So to reconstruct the actual encrypted data, I extracted each 64-bit integer and broke it down into its individual bytes (little-endian order), yielding an array of 8-bit hexadecimal integers like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

encrypted = [

0x09, 0x34, 0x2a, 0x39, 0x27, 0x10, 0x1f, 0x0c, 0x1d, 0x56, 0x6c, 0x5c, 0x51,

0x12, 0x15, 0x01, 0x08, 0x3e, 0x04, 0x18, 0x1c, 0x1e, 0x41, 0x5a, 0x52, 0x59,

0x12, 0x06, 0x06, 0x09, 0x12, 0x34, 0x15, 0x0b, 0x17, 0x6e, 0x54, 0x5c, 0x53,

0x12, 0x0e, 0x0f, 0x32, 0x15, 0x03, 0x11, 0x3a, 0x00, 0x5a, 0x4a, 0x4e

]

By extracting this encrypted array and applying the same XOR logic in a separate Python script, I was able to recover the plaintext — and ultimately, the flag.

Thoughts?

This challenge wasn’t about a traditional software vulnerability—it was more of a cryptographic oversight.

Still, this room was a fantastic introduction to binary analysis and XOR decryption in a CTF context. It really taught me to read between the opcodes, trust the tooling, and not underestimate the power of a hardcoded constant.